Every Wednesday night, the L-shaped intersection to the north of Leimert Park Plaza gets blocked off to make space for the Leimert Park Night Market, Powered by Black Women Vend. Vendors sell banana pudding, vegan burgers, and shrimp tacos while a DJ keeps customers dancing; later in the evening, an open mic gives MCs and musicians a chance to show off their chops.

All the vendors at the market are participants in Black Women Vend (BWV), a nonprofit that offers Black women food entrepreneurs the resources, training, and community they need to survive and thrive in LA’s competitive culinary landscape.

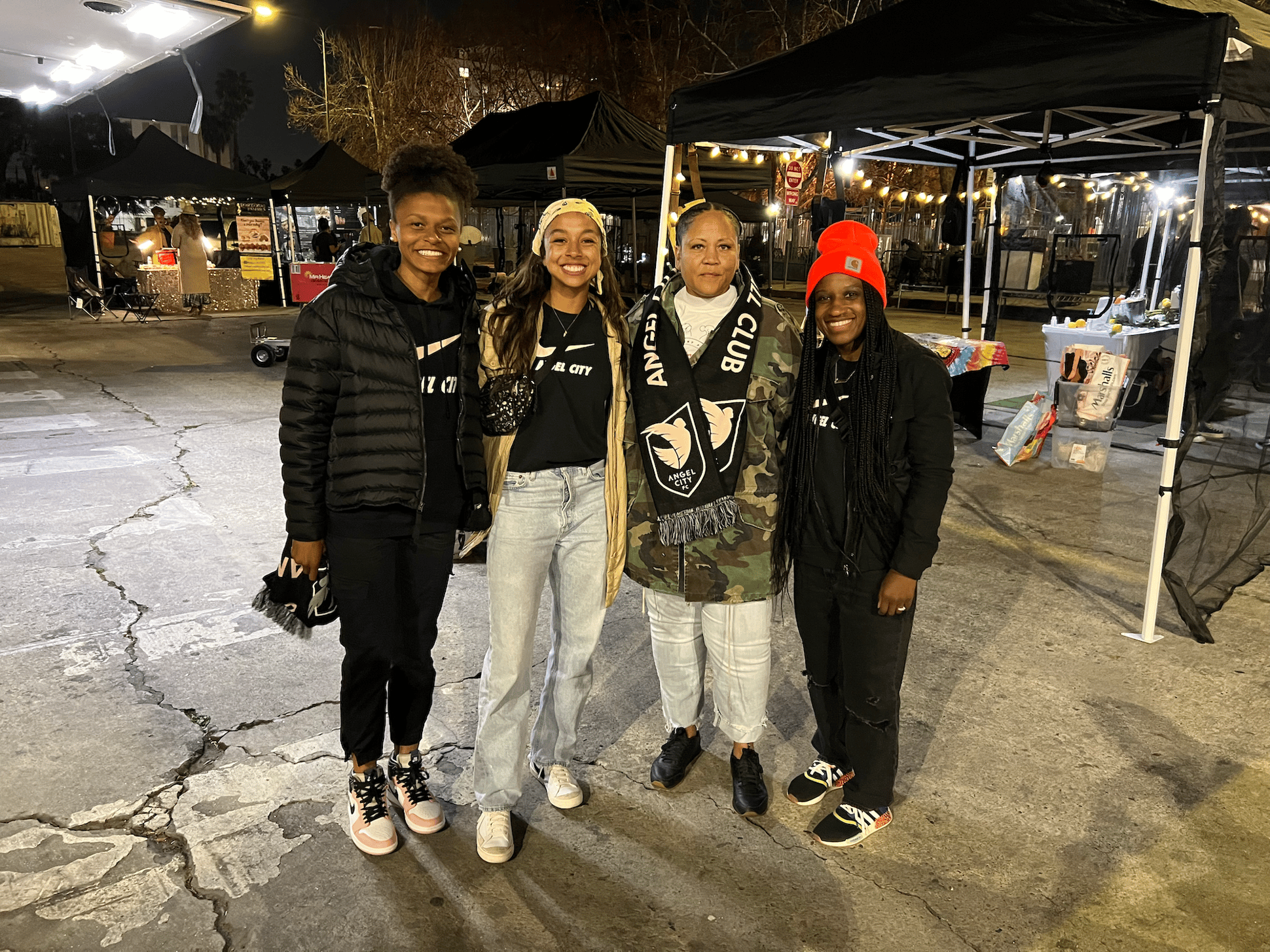

Last week, three Angel City players—Simone Charley, Madison Hammond, and Jasmyne Spencer—visited the market, sampling each vendor’s wares, chatting with the entrepreneurs and their customers, and showing off their skills on the dance floor.

“It's really, really hard to survive as a food business in LA,” BWV’s founder, Jennifer Laurent, explained to the players. “Even to be a street vendor, it's super expensive.”

The idea behind BWV is to get participants everything they need to go from operating as street vendors to opening brick-and-mortar restaurants and stores.

“We're taking the ladies through all the permits and licenses that they need,” Laurent said. “We're putting them through training. We have a restaurant consultant. The whole goal is to uplift and empower their businesses, and help their business increase their revenue… so if someone came to them tomorrow and said, ‘Here's a building for free,’ they have everything.”

Laurent, who works as a real estate broker, says the genesis of the Night Market was during the pandemic, when she would come to the park to set up a wireless hotspot and help people apply for stimulus money or unemployment. “The conversation transferred over to what street vendors need,” Laurent said, “and it grew from there.”

“When you go to all these different pop-ups,” she explained, “vendors have to pay a lot of money to participate. It's like $200–500 just to be part of the event. Then you have to get a health permit, so that's another $185. Then you have to buy your food. You're starting at a deficit every time you walk into an event. So [we said,] what can we do to help you get better?”

The initial round of city and county funding for the market was for a 12-week pilot program, but Laurent plans to keep reapplying for funding to continue and to expand for “as long as we can.”

The players relished the opportunity to talk with Laurent, support the vendors, and participate in the community. “Being able to come here and be a part of the Black community,” said Charley, “and hear about the Black women being supported and the vendors being here—it means so much to me.”

Leimert Park Plaza is at the center of the Black community in LA, both literally and figuratively. Sandwiched between Leimert and Crenshaw Boulevards, the neighborhood is bordered by Crenshaw and Baldwin Village to the west, and Jefferson and West Adams to the north, with Expo Park just a few miles to the east.

After World War II, together with Japanese Americans whose homes and businesses in Little Tokyo had been stolen during Internment, Black Americans from elsewhere in LA and across the country began settling in the previously all-white neighborhoods of South LA. Leimert Park itself was one of LA's first planned communities, and until 1948, racial housing covenants prevented people from renting or buying homes there.

Over time, Leimert—especially the neighborhood’s core, known as Leimert Park Village—became a hub of Black art and culture. Jazz clubs, performance spaces, and art galleries thrived there. Local artists and legends like Ella Fitzgerald and Ray Charles alike have called the neighborhood home; in the 90s, Project Blowed, an influential open-mic workshop and hip-hop crew affiliated with rappers like Aceyalone, Abstract Rude, and Busdriver, started weekly sessions at the KAOS Network art space.

“[Leimert] is the center of Black culture in LA,” Laurent told the players last week. “It’s a symbol of Black excellence.”

As the players enjoyed the culinary excellence on offer at the Night Market, Spencer called out the importance of shining a light on places like Leimert. “I feel like when you think of Black neighborhoods, you think of them as typically underserved communities,” she said. “So to know that this community is flourishing and it's Black owned, it's like proof that we can do it when given the opportunity.”

Laurent had that same feeling when she first experienced Leimert. Where she grew up, in the San Fernando Valley, hers was the only Black family on their block. “When my friends brought me out here,” says Laurent, “seeing Black people owning commercial property, Black people owning homes—not only in Leimert Park, but right next door in View Park and Baldwin Hills—it was a very motivating eye opener.”

“Coming into the Village is like being embraced,” she continued. “It doesn't really matter where you're from, what your story is. People will always be open.”

The players said they felt welcomed into that community right away. “I feel like [I’m at] home a little bit,” said Spencer. “I grew up in a predominantly Black neighborhood, and so as soon as I pulled my car in, I was like, ‘my people!’... It’s just a feeling of belonging.”

“I think that being Black is just about having community and having people who understand your experiences,” said Hammond. “My identity as a biracial woman is always something that's [been] challenging for me personally, but is something I've learned to really embrace… So to come here, to Leimert Park, where Black excellence is so prevalent and really championed, is really special.”

“If you come out on Saturdays and Sundays,” said Laurent, “there's drum circles, there's other vendors lining Degnan, [selling] cultural products, waist beads… We have drum makers, African mask makers. I mean, it’s just—Black!”

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the neighborhood finds itself at a crossroads as community members like Laurent are working to hold onto the area’s character, vibrancy, and—crucially—its Blackness, in the face of rising property values and the looming specter of gentrification.

COVID also took a toll on the Village; Laurent gestured to a row of boarded-up storefronts that were once thriving businesses. Work on the Metro K line running along Crenshaw Boulevard was another blow, with construction cutting businesses off from much of their customer base. “Even though we're not right on Crenshaw,” explained Laurent, “that's how you get into Leimert.”

The line, which opened in October, is a double-edged sword. On one hand, residents have improved access to public transit; on the other, the new access point renders the area more desirable to outside buyers.

Laurent is just one of many community members in Leimert, as well as nearby Crenshaw and Baldwin Hills, fighting to maintain the Black culture and community that define South LA.

In 2021, the community group Downtown Crenshaw lost their fight to buy the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza mall, which was instead sold to a white developer. What the group had hoped to turn into affordable housing, a medical clinic, and spaces for job training, conferences, and Black artists, will instead be redeveloped into a hotel, restaurants, and mostly market-rate apartments and condos.

The mall’s $140 million price tag was a sign of the times in the rapidly changing area. A 2014 LA Times article noted that between 2013 and 2014, median home prices in West Adams, Jefferson, and Crenshaw jumped more than 40%, as white home buyers from the westside, downtown, and Hollywood flocked to the once-maligned region.

As so often happens, what looks on paper like revitalization means displacement for longtime residents.

“The neighborhood is changing,” said Laurent. “There's a large amount of fear around here: is everyone going to be priced out? As a real estate agent, one of the first homes that I sold was on 43rd place. I got it for $350,000, and the property is over a million dollars now. As a lot of the older people pass away, their kids aren't able to afford probate, so they're losing property and the demographic is changing.”

It was in part with an eye to the north and the fate of the Baldwin Hills Plaza that Akil West, owner of Sole Folks, a clothing store on Degnan Boulevard, led a community push to buy the building he rented space in. After West and his partners secured $6.5 million in grants and loans, that building, which sits a block away from the Night Market, is now owned by West’s nonprofit, the Black Owned and Operated Community Land Trust.

When Laurent told the players the whole block behind them was Black-owned, they cheered.

“Obviously in the history of Black people in the US,” said Charley, “we don't really have that opportunity [to own real estate], and you don't really learn about communities that are Black owned. So hearing that, there’s a sense of pride and excitement, like—‘look at us!’”

The name Leimert Park Village isn’t just a nice-sounding moniker. It’s an ethos the community takes seriously. “We're a village and we operate under that concept,” said Laurent.

“There used to be more homeless people in the park,” she explained. “At the end of Wednesday evenings, we ask all of the ladies to donate a plate or two to make sure everyone in the park eats… Some of the guys that you see helping us set up [live on the street], and we make sure to pay them because we don't know what other income they have. We don't ask a whole lot of questions. When you show up and you want to help, we say, ‘okay, help us, and we'll pay you what we can.’”

In contrast with landlords and developers from the outside who might look at Leimert and see an opportunity to cash in, Laurent and other community leaders want economic growth by and for the Black community, which boosts local entrepreneurs at the same time as it nurtures the neighborhood as a whole.

On Degnan Boulevard south of 43rd Street, a “walk of fame” of plaques embedded in the sidewalk commemorates 32 Black artists who shaped the cultural life of the area. As a historic marker in the Village explains:

The pathway is called the Sankofa Passage, which refers to a phoenix-like bird of Ghanaian mythology that looks backward over its shoulder while in flight — a symbol of embracing the past while simultaneously going forward into the future. It is a concept that Leimert Park Village, with its penchant for tradition but also its openness to change, has always tried to make real.